Introduction

In the world of Argentine Tango music, few names resonate as powerfully as that of Julio de Caro. A pioneering figure in the genre, de Caro’s contributions have left an indelible mark on the landscape of tango. His innovative approach to composition and orchestration played a pivotal role in shaping the sound and style of Argentine Tango music, earning him a place of honor in the annals of the genre. Learn more about Julio de Caro’s life and career.

Early Life and Background

Born into a musically inclined family, Julio de Caro was destined for a life in music. His early years were steeped in the rich musical traditions of Argentina, providing him with a solid foundation upon which he would build his illustrious career. His journey into music began with the violin, an instrument that would become a key part of his musical identity.

Musical Career

Julio de Caro’s musical career was a journey of innovation and exploration. He formed his orchestra at a time when tango music was ripe for evolution. His unique approach to orchestration, characterized by a delicate balance of traditional and modern elements, set him apart from his contemporaries. His compositions, rich in complexity and emotional depth, pushed the boundaries of what was considered possible in tango music. Explore Julio de Caro’s discography.

Influence on Argentine Tango

Julio de Caro’s influence on Argentine Tango cannot be overstated. His innovative compositions and arrangements played a significant role in shaping the genre, ushering in what is now known as the Golden Age of Tango. His music, characterized by its emotional depth and technical complexity, expanded the expressive possibilities of tango, making it a vehicle for a wider range of emotional and musical expression. His work has left a lasting legacy, influencing generations of musicians and shaping the sound of Argentine Tango as we know it today. Listen to Julio de Caro’s music.

Sure, here’s how you can adapt the content to fit a Tango Dance and Music-centric blog:

Legacy and Recognition

Julio de Caro’s contributions to Argentine Tango have not gone unnoticed. Over the course of his career, he received numerous awards and honors, a testament to his talent and influence. But perhaps the most significant aspect of his legacy is the impact he had on future generations of musicians. His innovative approach to tango music has inspired countless artists, shaping the genre for years to come. Learn more about Julio de Caro’s life and career.

Discography

Julio de Caro’s discography is a testament to his prolific career. His albums and songs capture the evolution of his music style, offering a rich tapestry of sounds that reflect his unique approach to tango. From his early compositions to his later works, each piece offers a glimpse into his musical genius. Explore Julio de Caro’s discography.

Later Life and Death

After a lifetime dedicated to music, Julio de Caro’s later years were marked by a retreat from the public eye. Despite this, his influence on tango music remained as strong as ever. His death marked the end of an era, but his legacy lives on in the music he left behind.

FAQs

- Who was Julio de Caro?

- What is he known for?

- What was his impact on Argentine Tango?

- What are some of his notable compositions?

Conclusion

In conclusion, Julio de Caro’s impact on Argentine Tango is immeasurable. His innovative approach to composition and orchestration revolutionized the genre, influencing generations of musicians. His music, characterized by its emotional depth and technical complexity, continues to resonate with audiences today, making him a true icon of Argentine Tango. Listen to Julio de Caro’s music.

Based on the information gathered, it’s clear that Julio de Caro’s music continues to be appreciated and danced to in modern milongas and tango festivals. His compositions, characterized by their richness and musicianship, have left a lasting impact on the tango scene.

Appreciation of Julio de Caro’s Music in Today’s Milongas

Today, Julio de Caro’s music continues to be a staple in milongas around the world. His compositions, characterized by their rhythmic complexity and emotional depth, are particularly appreciated by dancers who enjoy the challenge and expressiveness of his music.

The style of tango danced to de Caro’s music is often more complex and interpretative, reflecting the intricate musicality of his compositions. Dancers often use his music to explore the more creative and improvisational aspects of tango, making his compositions a favorite among more experienced dancers.

Among the most played recordings of Julio de Caro at milongas and festivals are “Saca chispas”, “Flores Negras”, “Milonga de Mi Flor”, and “Boedo”. These pieces, with their distinctive rhythms and melodic lines, offer dancers a rich musical landscape to explore and interpret on the dance floor.

In addition, “Mala junta” and “La rayuela” are also frequently played at milongas, offering a glimpse into de Caro’s unique approach to tango music. These compositions, with their intricate arrangements and emotional depth, are a testament to de Caro’s innovative spirit and his profound influence on the evolution of tango music.

Appreciation of Julio de Caro’s Music Today

Julio de Caro’s music is still very much alive in the tango scene, with dancers appreciating the rhythmic complexity and emotional depth of his compositions. His music is often played at milongas, social dance events where people gather to dance tango. Dancers typically dance the Argentine Tango to de Caro’s music, a style known for its improvisational nature and emotional intensity.

Most Played Recordings at Milongas and Festivals

Several of de Caro’s recordings are popular choices at milongas and festivals. For instance, his milonga “Sacachispas” is frequently played and danced to. This piece was notably performed at the Torino Tango Festival in 2019, with dancers Fatima Vitale and Javier Rodriguez showcasing their skills to the rhythm of de Caro’s music. Another popular piece is “Saca Chispas,” which was danced to by Roxana Suarez and Sebastian Achaval at the TanGO TO Istanbul event in 2019.

Tango Style to Julio de Caro’s Music

When dancing to Julio de Caro’s music, dancers typically embrace the Argentine Tango style. This style is characterized by its close embrace, where the leader and follower connect chest-to-chest, and its intricate footwork, which often includes embellishments, syncopations, and pauses. The music of Julio de Caro, with its complex rhythms and emotional depth, lends itself well to this expressive dance style.

In conclusion, Julio de Caro’s music continues to be deeply appreciated in the tango dance community. His innovative compositions not only offer dancers a rich and complex musical landscape to explore, but also serve as a reminder of the depth and diversity of tango music. As such, his music continues to inspire and challenge dancers, ensuring his enduring legacy in the world of tango. Listen to Julio de Caro’s music.

WIKIPEDIA

Julio de Caro (Buenos Aires, December 11, 1899 – Mar del Plata, March 11, 1980), was an Argentine violinist, conductor and composer of tango.

early years

He was the second of the twelve children of the marriage formed by Matilde Ricciardi Villari and José De Caro De Sica and was born in a mansion in the Balvanera neighborhood on Calle de la Piedad (now Bartolomé Mitre) at the height of Azcuénaga in the city of Buenos Aires. Aires. They had married in Buenos Aires, they were Italian and linked to art: his mother had worked professionally as a singer and his father had studied music in Italy and worked at the La Scala conservatory in Milan.

From his childhood he was very close to his brother Francisco de él, who was a little less than two years older than him. Later the family moved to Bolívar street and then to San Telmo (now Defensa) at 200, in the neighborhood of the same name where his father set up a conservatory and a business selling sheet music and musical instruments that many musicians attended, for which the brothers grew up in contact with the musical environment of the time. He initially studied in a neighborhood elementary school and then when his family returned to the Balvanera neighborhood moving to a house in Mexico and Catamarca he continued studying first at the San José College and then at the Mariano Moreno National College while studying high school. In addition, in 1913 he began to help his father by giving theory and music theory classes.

His musical studies

Following his father’s directives, from a young age Julio De Caro studied piano while his brother Francisco played the violin, first with his father and then with David G. Bolia (who had studied at the famous conservatory in Naples, Italy, and founded in 1888 in Buenos Aires the Melani Conservatory, which currently (2008) works on Avenida Independencia and Rincón, under the direction of his granddaughter). At some point, however, they realized that they preferred each other’s instrument. Since they did not dare to ask their father directly, they did so with the mediation of his mother and obtained the parental consent to exchange the instruments they were studying.

Julio went to study with maestro Fracassi while Francisco entered the Williams Conservatory. In both cases, they were prestigious institutions and it was thus that they soon began to perform recitals, even in the Príncipe George’s Hall located on Sarmiento street, which was only reached with solid musical knowledge. Both the studies of the De Caro brothers and the recitals were of what the father called serious music, to the total exclusion of popular music.

In 1915 Julio participated in the current Liceo theater (then Lorea theater) as second violin in the orchestra of the zarzuela company, thanks to the businessman Arturo De Bassi, who was a friend of his father. Despite the fact that he asked that he not tell his father, he found out and in addition to forcing him to return the five pesos earned for that performance, he was punished for eight days in a corner on bread and water.

Francisco and Julio, however, had begun to go to places where the maestros Roberto Firpo, Arolas, Cobián and other musicians of their level played tango music and, secretly, began to read and practice it.

Start as a professional musician

In 1917, a group of friends who accompanied Julio in the Palais de Glace room came together to demand that he go on stage, for which reason the required man was compelled to take the place of the violinist in the Firpo orchestra, who lent him his instrument. , to perform a tango with her, receiving at the end the congratulations of the director and Eduardo Arolas who was present.1 Days later Arolas, who at that time was resoundingly successful, visited Julio’s father to propose his incorporation into his orchestra and the answer was negative (his father had decided that he should study medicine) but a little later Julio made his debut at the age of 18 and without his father’s knowledge, in the ensemble led by the bandoneon player Ricardo Luis Brignolo, temporarily replacing the main violinist.

Those two weeks of performance showed Julio what he surely already glimpsed, this is his tango vocation, and they decided him to accept Arolas’ request and it was so that a few weeks later a quintet was structured with Roberto Goyeneche on piano, Rafael Tuegols and De Caro on violin, and Manuel Pizarro and Arolas himself on bandoneon. Julio Mon Begin, his first tango, premiered with this ensemble.

When his father did not accept that Julio abandoned his studies and dedicated himself to popular music, he was kicked out of his house and Francisco followed the same path without expecting to be kicked out. The Arolas ensemble made successful presentations in downtown cabarets and cafes and in the summer season they traveled to Uruguay to perform in the municipal hotels of Montevideo, culminating in the performances at the Solís Theater where they animated Carnival dances. In that city Julio reunited with Francisco who had taken up residence there and worked as a pianist in movie theaters accompanying silent films and also in cabarets.

Both brothers, who received good remuneration for their work, also produced together and thus created the tango Mala pinta and later others such as Mi encanto, Pura labia, Don Antonio, A shovel, The countrywoman was good, Percanta arrepentida, Bizcochito, Gringuita and La Canada.

Upon returning in 1919, Arolas began a tour of the Province of Buenos Aires, but in the midst of it Julio De Caro and the pianist José María Rizzuti, who had replaced Goyeneche, had a financial disagreement with Arolas, separated from the group and returned to Buenos Aires. In this city they met with the bandoneon player Pedro Maffia who had left the Roberto Firpo orchestra for the same reasons and with the violinist José Rosito and formed a quartet that began their performances at the Café El Parque in Talcahuano and Lavalle. premiered his tango Pelele, Maffia and De Caro premiered Tiny and Rizzuti and De Caro premiered Pulgarín.

Some time later, and despite their success with the public, the ensemble dissolved amicably because its members had received proposals that satisfied them: Maffia returned with Firpo, De Caro and Rizzuti joined Osvaldo Fresedo’s first orchestra to perform in Pigall’s Casino. During the trip that Fresedo made to the United States in the mid-1920s to record the ensemble, he continued to perform there, but upon his return, Fresedo released them because he did not intend to rejoin the orchestra.

His performance by the Minotto Di Cicco orchestra

Soon after, Julio traveled to Montevideo to do a series of performances with Enrique Pedro Delfino. When they ended in 1922 he remained in Montevideo where shortly after he joined the bandoneonist Minotto Di Cicco’s orchestra. Francisco later joined the orchestra to replace pianist Fioravanti Di Cicco, and this was the first time the brothers had worked together in a professional ensemble. Julio premiered his tangos there La Farándula, Maridito Mío, Milonga Corrida, Jardín florido and Minotito and at the same time the De Caro brothers composed La mazorca and El bajel.

Julio’s professional relationship with Minotto ended on excellent terms when the former accepted the proposal to join the trio made up of Antonio Gutman on bandoneon, Roque Ardit on piano and Pedro Aragón on violin with the aim of improving the style of playing with his knowledge of music. set execution.

In the Cobián orchestra

At the end of the summer of 1923, Julio returned to Buenos Aires and joined the orchestra that was being organized by the prestigious pianist and composer Juan Carlos Cobián, a group that went down in history because it meant the direct antecedent of the most important instrumental transformation movement in tango. 2 made up of Juan Carlos Cobián (piano), Agesilao Ferrazzano and Julio De Caro (violins), Pedro Maffia and Luis Petrucelli (bandoneons) and Humberto Costanzo (double bass). They performed at the Abdulla Club of Galería Güemes and recorded for RCA Victor, among them De Caro’s songs La machona, Astor, Carita de ángel and La confession.

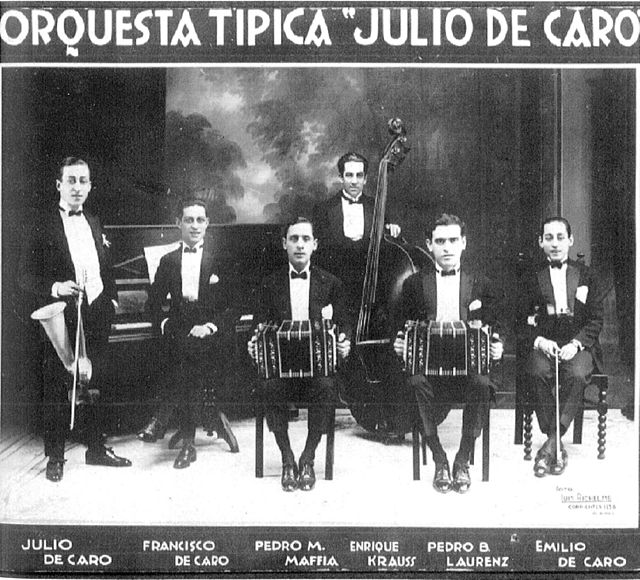

Play for high society

In December 1923, a businessman offered Francisco De Caro a group of five or six musicians to perform for the year-end parties at meetings in various high-class residences, receiving the sum of eight hundred pesos per dance, which was very high. for the time. Thus, he joined Julio, who was out of work because Juan Carlos Cobián had dissolved his ensemble, Emilio De Caro and the double bassist Leopoldo Thompson plus Maffia and Petrucelli. Not only were the presentations very successful, but also the impeccable clothing of the musicians (tuxedo, hard-fronted shirt and dovetail collar) plus the impeccable conduct they showed contributed to the definitive acceptance of tango in Buenos Aires high society.

With the main purpose of continuing together since they felt comfortable in the orchestra (which still had no name) they agreed to play at the Colón café on Avenida de Mayo and Bernardo de Irigoyen where they were paid thirty-five pesos for each afternoon of performance and participate in experimental programs on Radio South America, the latter for free because they were looking for promotion.

However, despite their wishes, the musicians decided to end the performances in a few weeks because the income was insufficient but before that they received the new proposal to play at the L’Aiglon hall in Florida between Cangallo and Bartolomé Miter during the Carnival dances with a remuneration that allowed to form an orchestra of twenty musicians. They agreed that although the orchestra would remain nameless as up to now, it would be announced under the conduction of Julio De Caro.

The orchestra was formed in this way: Julio, Alberto and Emilio De Caro, Lorenzo Olivari, Esteban Rovati, Bernardo Germino and Antonio Arcieri on violins, Pedro Maffia, Luis Petrucelli, Ricardo Brignolo, Luis D´Abraccio, Ángel Danesi, Nicolás Primiani, Miguel Orlando and Luis Minervini on bandoneons, Francisco De Caro and Roberto Goyeneche on pianos and Leopoldo Thompson and Olindo Sinibaldi on double basses.

When the Carnival dances were over, Julio and Francisco returned to the presentations at the Colón café and Count Chikoff appeared there to offer them a contract of six thousand pesos per month for the sextet to play at the Vogue’s Club, which would organize tea parties designed for high society in the premises of the Palais de Glace. At the same time they received the offer to record at RCA Víctor.

Shortly before the debut, Maffia and Petrucelli decide to leave the orchestra, incidentally irritated by a Vogue’s Club ad announcing “Julio De Caro’s” orchestra. The group urgently needed his replacement, as the day of the debut was approaching. Almost on the eve Maffia, who had just lost a lot of money gambling, offered him to return to the complex until another location was found, which Julio accepted although their personal relationship continued to be strained. On the other hand, through the mediation of the bandoneon player Enrique Pollet he met, listened to and immediately hired Pedro Laurenz.

Laurenz’s entry did not come with good omens. Until that moment he was practically a stranger that he was going to play as second bandoneon player for an already established musician such as Pedro Maffia who, moreover, practically did not speak to the orchestra director. However, not only did his presentation have no flaws, but he also created a friendship with Maffia and they formed one of the most famous bandoneon duos in the history of tango.

Julio De Caro and Maffia mended their relationship to the point that they lived with Francisco in the same apartment and the orchestra definitively took the name of the former. A contract came out immediately to inaugurate the Chantecler cabaret on Paraná street, where Julio De Caro premiered his tangos Adiós Chantecler and Buen amigo.

On April 10, 1925, they returned to the Palais de Glace to perform in what was now the Ciro’s Club, which had become a center for high society, to the point that the Prince of Wales received a gala reception on his visit there. to the country.

The violin-cornet by Julio de Caro

Paul Whiteman, the famous jazz musician, was an RCA Victor artist, like Julio de Caro, and he really liked the tango that he had had the opportunity to listen to when Juan Carlos Cobián was in the United States. Upon hearing De Caro when he himself was going to make recordings at the Víctor studios, he suggested to the recorder that they leave him the violin-cornet with which classical soloists recorded that they were repairing because according to his criteria it had a new concept. , modern. The innovation consisted in that to increase the volume of the violin a cornet was attached to it, hence its name, which brings the instrumental sound closer to the human voice, giving it a nasal nuance. When the company representative traveled to Buenos Aires, he took the violin to De Caro, offering him that the price would be deducted from the rights to collect. The musician at first did not want to use it but later accepted it and although it was difficult for him to adapt to it, in the end it was well used to give the orchestra a special sound, becoming known as the “violin-cornet of Julio de Caro”.

Continuity in action

At that time the double bassist Thompson died suddenly and Hugo Baralis (father of the well-known violinist of the same name) replaced him.

Then followed performances by the orchestra at the Richmond Florida, the Tigre Hotel and the Plaza Hotel. In the Carnival of 1926 De Caro returned to animate the dances at the 18 de Julio theater in Montevideo with some changes in the orchestra: Baralis was replaced by Olido Sinibaldi and the violins of Manlio Francia and Antonio Arcieri and the bandoneons of Enrique Pollet were added. and Antonio Romano.

Back in Buenos Aires he was hired to perform at the Select Lavalle cinema, an opportunity in which the musician of symphonic formations Enrique Kraus replaced Sinibaldi, while silent films were being shown. The reality is that the public that came was not interested in what movie was being shown, but rather that they were going to see and listen to Julio De Caro. In that season the tango Guardia vieja that De Caro dedicated to the president Marcelo T. de Alvear was the great success. In the middle of that year Pedro Maffia amicably separated from the orchestra to form his own ensemble, for which Pedro Laurenz was promoted to first bandoneon and Armando Blasco joined in his place.

Assuming the role of impresario with jazz player Gordon Stretton, De Caro performed with great success during the 1927 Carnival dances at the Avenida theater and the Callao cinema at the same time. Then, between May and September, he went to the Copacabana Palace Hotel in Rio de Ja

neiro adding the singer Luis Díaz to the orchestra and in that season he premiered Tierra querida, Copacabana and Olimpia. Returning to Buenos Aires and to Select Lavalle, he premiered Mala junta written in collaboration with Pedro Laurenz.

For the Carnival of 1928 he performed at the Ópera and San Martín theaters and later continued with performances in the cinema. There the double bassist Vicente Sciarreta entered and De Caro premiered Boedo and Moulin Rouge. Towards the end of 1929, José Niesow replaced Emilio De Caro and the orchestra animated the fashion shows that were held in the Ciudad de México store located in Florida and Sarmiento while at the same time recording for the Brunswick label. Throughout 1930 he performed at the Cine Real on Esmeralda and Corrientes streets and at the 1931 Carnival at the Cervantes National Theater. At that time he released the waltzes Ilusión de pierrot and Amelia and the tangos Tierra adentro and Batida nocturna.

Europe tour

Julio De Caro and his orchestra embarked on March 4, 1931 for Europe and began their performances at the Palais de la Méditerranée in Nice. Presentations in Monte Carlo, Cannes, Turin, Genoa and Rome followed. The orchestra pleasantly surprised the public, first for the impeccable presentation of the musicians in tuxedos and then for their artistically stylized interpretations and with an instrumental richness unknown up to now in Argentine ensembles. In Rome, Prince Humberto of Savoy and his wife María José of Belgium witnessed his performance. In Turin, his presentation at the Opera Theater was broadcast by Radio Torino and captured in Buenos Aires by Radio Splendid.

Paris was the culmination of the tour: a performance at the Sorbonne at the invitation of the Argentine ambassador Tomás Le Bretón, a successful presentation at the Empire, a contract to play at one of the lavish receptions at the Rothschild Palace and filming at the Jointville studios of the Paramount for the film Luces de Buenos Aires directed by Manuel Romero with the performances of Carlos Gardel, Pedro Quartucci, Sofía Bozán, Gloria Guzmán and Vicente Padula among others. At the Palais de Mediterranée among those who attended his performance were Carlos Gardel and Charles Chaplin.

Return to Buenos Aires and new orchestral formation

In Buenos Aires, with the advent of talkies, orchestras began to be displaced from theaters. De Caro restructures his orchestra and during 1932 he performs on the stage of the Astor cinema and later in the interior of the country on an extensive tour. The new formation is the following: Julio De Caro, Sammy Friedenthal, José Niesaw, Simón Resnik and Vicente Tagliacozzo on violins, Pedro Laurenz, Armando Blasco, Alejandro Blasco, Calixto Sallago and Aníbal Troilo on bandoneons, Francisco De Caro and José María Rizzuti on piano, Vicente and José Sciarreta on double bass and the singer Antonio Rodríguez Lesende.

First National Tango Championship

At the initiative of Malevo Muñoz, the Crítica newspaper of Buenos Aires organized the First National Tangos Championship to be held at the Luna Park stadium, in which the most prestigious orchestras of the time competed, except those that were not authorized by their recording labels. . The vote, carried out by the public with a ballot attached to each entry, gave the Julio De Caro orchestra the winner. The orchestras of Edgardo Donato, Juan Pedro Castillo, Pedro Maffia, Ponzio-Bazán and Anselmo Aieta were located in the following places. In a later composition contest, Julio De Caro won first prize with his tango El mareo.

After the Carnival and due to economic disagreements, all the members of the orchestra, except his brother Francisco, broke ties with it and formed another led by Pedro Laurenz. Julio then organized a new formation with Luis Gutiérrez del Barrio, Mauricio Salovich and Julio himself on violin, Francisco De Caro on piano, Carlos Marcucci, Romualdo Marcucci, Gabriel Clausi and Félix Lipesker on bandoneon and Francisco De Lorenzo on double bass.

At the Colon Theater

In 1935 De Caro formed an orchestra of forty teachers for the Carnival dances organized by the Municipality of Buenos Aires at the Teatro Colón, alternating the stage with the jazz of Eduardo Armani. On that occasion the tango Coquito by maestro Carlos López Buchardo premiered.

With the Radio El Mundo Symphony Orchestra he performed, in 1936, at the Opera Theater, with “La evolución del tango” with works from 1870 to 1905, the second from 1905 to 1935 and the third, and last, with themes from 1935 onwards. One afternoon, at the end of one of those morning concerts, his parents were there and there was a reunion and reconciliation. His father would pass away in 1950 and his mother eleven years later.

In 1937 he appeared in Viña del Mar (Chile), directing his International Melodic Orchestra with the singer Paloma Efrón “Blackie” and the singer Edmundo Rivero.

In the 1930s he organized sets of larger dimensions, in which he included a greater or variety of instruments, which in part caused some fading of his original style. Despite having renewed tango in the 1920s and imposing a style to which almost all tango orchestras after the 1920s would respond to a greater or lesser extent, it failed to keep up with the rapid evolution that occurred in the 1940s. At the end of this decade, however, he returned to the scene with a very renewed style, typical of this time, but this stage of his career did not last long, retiring from orchestral conducting definitively around 1954.

Julio De Caro’s work as a composer was very important, highlighting songs such as El Monito, Boedo, Mala Junta, among others. In essence, the fundamental contribution of Julio De Caro’s sextet was the incorporation of a refined style in the orchestral interpretation of tango, a style that combined all the richness of European academic music with the rhythm and canyengue typical of the genre. His interpretations are characterized by the frequent inclusion of solo violin or piano passages, as well as countersongs between two violins or between violins and bandoneons. This difficult synthesis was successful and also allowed De Caro’s orchestra to become the favorite of Buenos Aires high society.

Retirement

In 1954 he abandoned artistic activity almost at the same time as his brother Francisco. At the request of Ben Molar he composed in 1954 together with Nicolás Cócaro the tango Un silbido en el Bolsillo for project 14 with Tango. In 1975, again at the request of Ben Molar, he composed together with Ernesto Sabato, Cátulo Castillo, Florencio Escardó and Leopoldo Díaz Vélez, among others, for the album “Los 14 de Julio De Caro”.

December 11 was declared National Tango Day because on that date, although in different years, Carlos Gardel and Julio De Caro were born. That day in 1977 when he turned 78 and, in commemoration of the first “National Tango Day”, he received a tribute at Luna Park with the participation of the orchestras and singers of the time and 15 thousand people sang his happy birthday. It was the last time he was on stage.

In 1921 Julio De Caro had married in Uruguay and from his brief marriage before separating, his only daughter, Beatriz, was born. In 1959 he married Cora Ambrosetti for the second time, coming from a family well known for her anthropological and ethnographic studies.

He died in Mar del Plata on March 11, 1980 and his remains are in the Chacarita cemetery along with those of his brother Francisco de él.

De Caro and the cinema

De Caro worked in the cinema in the films La barra de Taponazo (1932), Petróleo (1940), Así es el tango (1937) and El canto cuenta su historia (1976); He composed the music for Sergeant Laprida died (1939), was musical director in Las luces de Buenos Aires (1931) and his theme Orgullo criollo is incorporated into the film Café de los maestros.

The music of Julio De Caro

Julio De Caro is considered in the history of tango as a musician who “made an era”. Most likely his influence on other musicians is greater than the public acceptance of him.

De Caro’s recordings are orchestral in sound, in the “classical” sense; that is to say: much more polyphonic than his contemporaries and with dynamic nuances of incredible prolixity. As a composer and as an arranger, De Caro brings to a greater degree of elaboration and subtlety the resource -usual in tango- of the countermelodies executed by the violin; usually the tangos composed by De Caro (such as Boedo or Mala Junta) expose one of the themes first, and the second or third time that the violin (or violins or strings) appears plays a melody on the theme already exposed in the foreground , which happens to be in the background. He also uses -in an attitude that can be considered avant-garde- foreign timbres to tango, such as laughter drawing a melody (in Mala Junta) and curious shouts on the tango El monito.

As a composer, De Caro’s tangos move with a more elegant spectrum of harmonic and melodic resources; the same thing happens in his role as arranger and even in that of performer. This appropriation by tango of elements belonging to cultured music -or this appropriation of tango by composers and social strata that revered European music- is one of the most accepted facts in the history of tango, to the point of being talked about of a “Decarean era” and of considering Julio de Caro as one of the most important musicians (or as one of the precursors) of the so-called “New Guard”, a concept that is itself controversial.

The singers of Julio De Caro

These are the singers who played in his orchestra:

Felix Gutierrez (1927/1928)

Lito Bayardo (1929)

Luis Diaz (1929/1932) (1938/1939)

Pedro Lauga (1929/1932)

Juan Lauga (1929/1932)

Teófilo Ibáñez (1929/1932)

Carlos Marambio Catan (1931)

Antonio Rodríguez Lesende (1932)

Edmundo Rivero (1936)

Lydia and Violet